Jim's Philosophy of Trade Secrets

The purpose of my work is to elevate trade secret practice to equal the attention and respect paid to the “registered” IP rights: patents, copyrights, trademarks and designs.

Working in this field since the early years of Silicon Valley, I appreciate the powerful but often evanescent commercial value of information. Traditional IP practitioners are comfortable with the statute-based, relatively predictable world of the registered rights, which are negotiated with the government and described in an official certificate. But trade secrets, encompassing all of a company’s useful data, are ubiquitous in the modern enterprise, and often they aren’t defined until there’s a dispute about them.

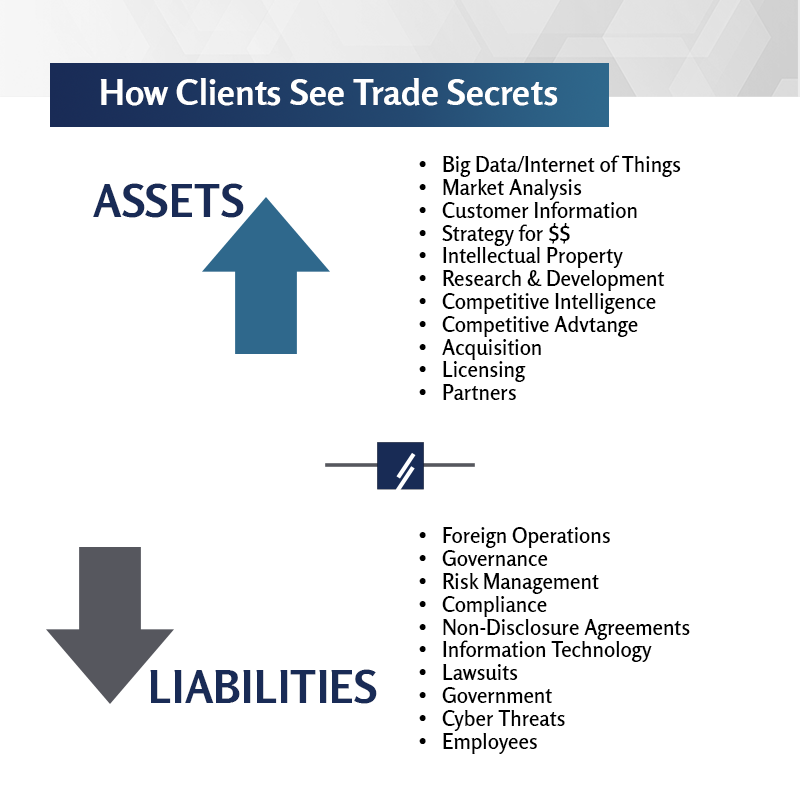

I aim to contribute to better understanding, within both the legal and business communities, about the nature of this increasingly valuable but vulnerable asset class. For my clients, I do this by applying my experience and judgment to dispute assessment and resolution, and by helping companies design and implement strategies to manage their information assets to minimize loss and contamination and to build enterprise value.

Within the broader community, I am privileged to serve as Chair Emeritus of The Sedona Conference Working Group on Trade Secrets, a think tank of practitioners, judges, scholars and members of the business community working to find consensus and advance development of the law. Through this work, coupled with my teaching and writing, I hope to promote increased awareness of an area of intellectual property that is too often neglected.

Because trade secret issues are not siloed by geography or IP discipline, I often find that my experience as manager of an international organization, coupled with my deep understanding of patent law and practice, gives me a unique perspective on trade secret cases and projects.

Drivers of Policy

Unlike employment law, trade secret practice doesn’t require that you represent only management or labor. Sometimes when people ask me about my litigation work, I reply that I “sue thieves and defend entrepreneurs.” There’s an important truth in that joke: trade secret law exists in the space between legitimate competing interests. Employers need to be able to trust their employees with access to sensitive data, and employees need new job opportunities to further their careers. The target of a potential acquisition has to be comfortable that its secrets won’t be misused if the deal falls through, and the other company needs assurance that it can continue to pursue independent projects.

Trade secret law was developed by judges over the last two centuries, to recognize and mediate these opposing interests. Courts understand that companies won’t invest in innovation if they don’t enforce promises of confidentiality, and they are equally aware of the individual and social consequences of interfering with the free movement of labor.

No matter the nature of the transaction or controversy, trade secret law is about ethics in business. When there is a dispute, judges and juries view the drama through a moral lens. This is one of the reasons I have always encouraged my law school students to get involved in trade secret litigation: the facts are interesting, and the lawyers can make a big difference with the advice they give their clients.

"James Pooley has a proven track record in intellectual property and a depth and breadth of experience that is truly exceptional. Many look to him as a close and trusted colleague and friend — someone to turn to for sober, perceptive and spot-on advice."

IAM Strategy 300

naming Jim as one of The World’s Leading IP Strategists

Trade Secret Disputes

Compared to other forms of intellectual property, trade secret cases are distinctive in their focus on fault. A theft, or a profound breach of confidence, has been alleged, and reactions include anger, resentment, jealousy, abandonment and scapegoating. In some ways, it can look like a bad divorce.

In spite of this intense emotional component, most trade secret disputes are settled, usually through mediation. Indeed, the parties’ passions often provide clues to a resolution. For the lawyers, however, settlement presents the unique challenge of acting simultaneously as advocate and as advisor, providing sober and clear-eyed assessments to inform the negotiations. Sometimes the situation is sufficiently delicate that independent counsel can better provide that advice.

For cases that can’t be settled, the litigation process has to be managed sensibly, in a way that doesn’t give rein to the emotions of the parties (or their lawyers, who sometimes don’t behave as they should). Because fault (and therefore intent) is an element, because of the broad and ambiguous sweep of confidential information, and often because of how much is at stake, these cases are typically hard fought. Similar to mediation, there can be value in engaging a private “special master” to help the court control the process and keep expenses down.

In any event, because the vast majority of them never get there, taking a trade secret case to trial requires careful planning by experienced counsel. Applying seasoned judgment, sometimes by bringing in a “second pair of eyes” to act as co-counsel, can improve efficiency and outcomes. As any experienced lawyer knows, it is the story that matters; but without sufficient preparation the story you can tell at trial is not likely the one that you thought you were going to present. Trade secret cases are notorious for surprises that can shift how the litigants are viewed by the jury. So charting a strategy for the case requires anticipating possible twists and turns, and being prepared.

View Jim's Testimony on the Defend Trade Secrets Act

Watch Now

Learn About Jim's Services as Litigation Co-Counsel

Learn More

Management of Trade Secrets

Business owners contemplating their data assets can sometimes feel like the blind dog in a butcher shop: they can’t figure out where to start. The sheer amount of potentially useful information is overwhelming, and trying to organize it can seem like trying to boil the ocean. Based on my experience, this is when denial and justification take over:

- We haven’t seen a problem, so there can’t be much risk there anyway.

- We have an open access culture, so locking things down won’t work.

- It’s too time consuming and expensive.

- It’s too hard to get buy-in from top management.

And yet. We know that intangible assets account for over 85% of most public companies’ value, and that the majority of businesses rely on secrecy more than any other form of IP to protect their competitive advantage. And all this valuable data resides on inherently insecure networks while much of it is carried around in smartphones by people who may not be here next month. Besides that, we have to entrust a lot of it to our supply chain or various business partners. Isn’t it important to keep track of all that?

I understand the ambivalence. Back when I started in this field in the early 1970s, information security required only that you guard the photocopier and watch who went in and out the front door of the building. Times have changed dramatically, as we all know. The risk environment is completely different.

And that word “risk” is the key to resolving those concerns and hesitations about proactive trade secret management. When I ran the international patent system in Geneva, we handled about 200,000 confidential applications every year, and each one had to be maintained as a secret until the 18-month clock ran for publication. Getting that wrong and publishing early would have been catastrophic for the organization (and our customer). Calculating a fee incorrectly, not so much.

So the good news, in my view, is that prudent trade secret management begins with classical risk assessment, which is something that virtually all businesses do already. Those who manage each business unit or functional area know what are the “crown jewel” assets and what are the bad things that could happen to them. That’s where an effective trade secret program starts, and it can be implemented by any company no matter its size or what industry it’s in. You don’t have to inventory every piece of data in the company, and it doesn’t have to take long or be expensive. There are even tools available to help you categorize and catalog what you have, so you can better decide how to protect it and how to use it in ways that enhance enterprise value.